New Horizons for Public Participation at COP24

19.12.2018

Participation played a key role at this year’s UN Climate Change Conference COP24 in Katowice.

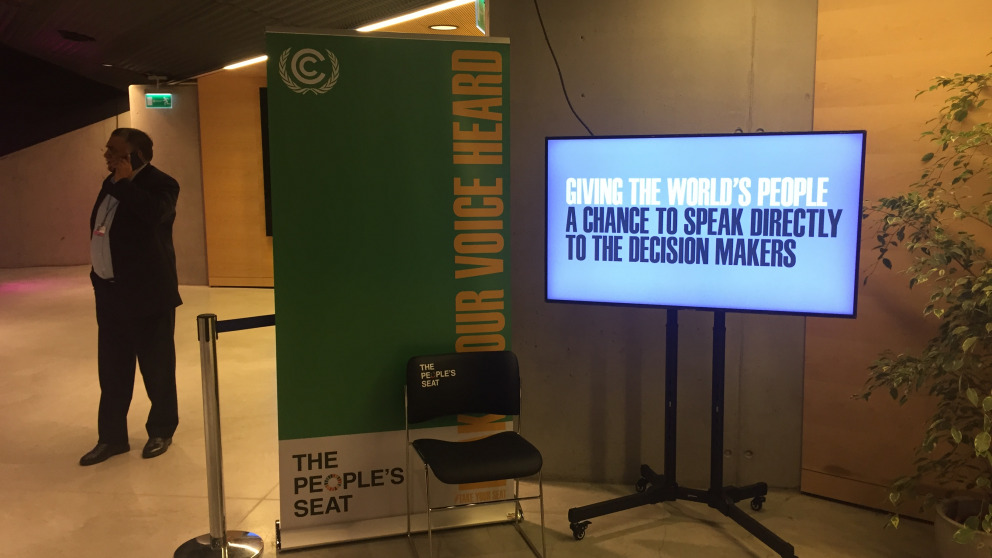

On the second day of COP24, Sir David Attenborough lent his signature voice to deliver the People’s Address before a full COP plenary. The address consisted of a two-minute video collage of social media video recordings, tweets and posts published under the #TakeYourSeat hashtag in the months prior and addressed to decision-makers at the summit.

Media

People's Seat Address

In a recent research article I examined the limitations and opportunities for the participation of those most affected in the climate negotiations on loss and damage from the perspective of international law. One of the principal and sobering findings was that there currently exists no real space for those most affected by climate change to share their experiences of living with loss and damage with those making the decisions that shape their present and future lives and livelihoods.

So at first glance the People’s Seat seemed an exciting new idea. The opportunity for those unable to join the negotiations, especially the people whose voices have gone unheard for so long to be granted a seat at the table is a major, if not, revolutionary development. And the words of Sir Attenborough seemed to promise no less, suggesting the seat “will be placed at the UN Climate Change Conference COP24 and will allow you and millions around the world an opportunity to join virtually and speak directly to the decision-makers at this crucial time. This is our opportunity to collectively make a difference. To have our voices heard. Together, we can send a message to the world's leaders they can't ignore, to act now.” Yet when put into practice, the People’s Seat began to look a lot less like an ambitious reform proposal and more like what it truly is: a chair.

Following the address, the chair could be found at the top of the escalators after entering the main lobby of the conference venue, where it remained, vacant, and removed from the negotiation rooms, for the better part of the two weeks.

It was there too, that I had an opportunity to speak to a representative of Grey London, one of the partners working with the UNFCCC Secretariat on the People’s Seat. He informed me that the initiative has a combined reach of 1.3 billion people through coverage on Twitter, Facebook and other social and broadcast media. But how can this many people be effectively engaged when ultimately their diverse voices are boiled into a two-minute video limited to short, snappy soundbites?

In the meeting rooms at the Spodek Arena in Katowice, I repeatedly heard the words “Party-driven process”. The age-old mantra muttered by the faithful negotiator in a multilateral, predominantly intergovernmental process where State Parties have the final say. States set the agenda. They decide the rules of the game. They can change the rules if they so agree. They can exclude observers from meetings at a whim. I am always reminded of my first exposure to a multilateral UN negotiation setting, in a full plenary including observers, when, for a whole thirty minutes, not a single Party would take the floor. After several attempts by the Chair to get the ball rolling, finally one Party responded by requesting ‘informal informals’ – a negotiating setting where normally only Parties with an interest in an issue consult informally to resolve it. The Chair agreed, and all Parties from the plenary moved into an adjacent smaller room, leaving behind the observers and intergovernmental organisations.

Personally, I think creative solutions like the People’s Seat are a stab in the right direction. Whether by design or coincidence, the People’s Seat raises awareness of the absence at the negotiation table of those who are most adversely affected by climate change. Of course, NGOs participate as observers at these summits, and one could argue that affected citizens are represented through their country delegations, themselves at times composed of affected persons (take the example of small island developing states, SIDS). But time and time again the deliberations and outcomes under the UNFCCC have frustrated the interests of those representing the most affected, due in part to limited speaking and non-existing voting rights (in the case of observers) and asymmetries of power in the negotiations (as in the case of Least Developed Countries and SIDS).

Another way to bring the experiences of those most affected by climate change into the negotiations is storytelling. During COP24, the NGO alliance Climate Action Network (CAN) launched a new segment called “Voices from the Frontlines” in its daily ECO newsletters, which I had the pleasure of co-editing. The ECO newsletters are published online and distributed onsite every morning, have large readership among COP delegates, and are appreciated for their often cynical ‘tell-it-like-it-is’ approach.

As 15-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg told delegates at COP24 in her address, “If solutions within the system are so impossible to find, maybe we should change the system itself.” So perhaps the UNFCCC can also learn something in terms of participation from initiatives like the Virtual Summit organised by the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF). The 24-hour-long conference held in November took place entirely online, allowing anyone with an internet connection to participate, with a view to “demonstrating our determination to reducing emissions through the creative application of readily available means, and to increase transparency and inclusivity while conserving scarce resources.”

But participation was a hot topic during COP24 for another reason. During the summit, several accredited NGO observers were denied entry into the country; some were detained, subjected to extensive questioning and prevented from travelling to Katowice. In a briefing with civil society observers, the Polish COP Presidency responded that border officials were only following the rules and the individuals concerned were either blacklisted as a “threat to the public order” or did not have a valid passport. These actions were preceded by a law issued by the Polish government ahead of the climate summit on the pretext of ‘safety and security’, which authorised Polish police to collect personal information on COP24 participants without their consent and banned spontaneous demonstrations in Katowice for the duration of the conference. Senior UN human rights officials expressed their concerns over how this legislation might infringe internationally protected civil and political human rights. I also had the opportunity to walk alongside chanting activists and concerned citizen in the Climate March, and felt rather uneasy being surrounded by a sea of riot police armed with shields and tear gas canisters.

Our IASS colleague and Humboldt Climate Protection Fellow, Adrian Martinez, has recently undertaken research on the role of public participation as a human right in the context of climate governance. At COP24 I also had the pleasure to moderate an official COP side event on “Public Participation in Climate Decision-making”, which was co-hosted by the Latin American NGO La Ruta del Clima, of which Martinez is the director, with a diverse panel including representatives from Argentinian, German, Costa Rican and international NGOs as well as the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR). One of the key takeaways from the panel concerned the need for stakeholder reform under the UNFCCC and the importance of human rights-based approaches in climate decision-making at all levels.

In the end, the People’s Seat certainly wasn’t the only quirky gimmick at COP24. A crowdfunding installation by VISA in the conference lobby allowed passers-by to repeatedly tap a credit card to effect a 3EUR donation to the Adaptation Fund. The message was perhaps a mix of bitter cynicism, raising awareness of the lack of finance for adaptation, and awkward self-promotion.

Next year COP25 will be held in Chile with a preparatory meeting in Costa Rica. Incidentally, Costa Rica is the birthplace of the Escazú Agreement, a new regional treaty expanding the human right to public participation in Latin American and the Caribbean. Perhaps the Costa Ricans can influence the agenda of COP25 towards greater inclusion of human rights and public participation in the UNFCCC and in the implementation of the Paris Agreement.